The meeting story of Orris Foss and Elowen Hale, and what grew between them—quietly, and by hand.

Chapter I: What Holds

Grief settles into corners.

Foss didn’t often weep, but he’d cried that morning. Quietly, behind the shed, where the rain barrel used to be.

He’d found the stone his mother, Sorrel, had set by the hearth, the way she touched it each time she passed. His father, Harn, had died just days before, and this was her way of keeping him near.

His mother wept often, and without shame. She wept when the soup boiled over. When she dropped the spoon and it clattered. When she lit the candle on the window-sill and whispered something Orris couldn’t quite hear.

Now she wore the pendant. She’d called it beautiful—pure, she’d said—and pulled him close with both arms when he gave it to her.

But it was the way she reached for it now, in quiet moments, fingers resting at the edge of her collar, that told him he’d chosen well.

It wasn’t just the piece. It was the hands that made it.

He’d been thinking about those hands all morning.

Chapter II: Pressed Into Silver

A meeting shaped not by intention, but by the pause before speech.

The morning was clear when Foss had arrived at Embel Rise. That bright, watery kind of spring where things feel scrubbed clean, too clean, as though someone had swept the sky too thoroughly. He kept to the outer lanes of the craft quarter, where the stalls were simpler and the signage was wood-burned rather than gilded.

He hadn’t come for anything grand. Just something that would hold. The finest he could afford, yes—but not in polish or prestige. In meaning. In weight.

The apprentices’ market ran along the west wall, little pop-ups under canvas, arranged by guild. Silver, glass, dyed felt, tooled leather. He passed most without stopping. He had an eye for the Evergild’s work and knew how to unsee its polish.

The silver stall was small—three boards laid over crate stands, neat rows of pendants and pins. Most were fine work: symmetrical, poised, designed to please the journeymen who’d be assessing them.

But one piece near the end stopped him.

A pendant, shaped like a pressed apple leaf—two, in fact, overlapping slightly. Not quite symmetrical. There was blossom too, faintly raised, half-finished. The engraving didn’t follow the typical Evergild geometry. The central vein was slightly crooked, and the loop had been set off-centre. But it held together. More than that—it sang.

“Now, this one’s alive,” he said, gently. “Is it yours?”

The apprentice behind the table looked up. She had deep brown eyes, a serious face, and strong fingers smudged with polishing compound. She didn’t smile.

“Yes.”

He picked it up. Turned it once in his hand. The edge was imperfect in a deliberate way—like she’d meant the line to shift, but hadn’t explained it to the metal.

“It doesn’t follow the old pattern.”

A pause. “It wasn’t meant to.”

He looked up, and she was watching him now. Not guarded. Just… tilted slightly inward, like a branch bent under the weight of its own leaves.

He asked about her process. She answered plainly—melting point, the curve warping when she fired it too long. Her voice was low, shaped by thought. Every reply seemed to take a moment longer than most people would wait, but she always gave the whole of it, not just the surface.

He liked that. He can tell she isn’t used to conversation like this—off-script, uncertain, real.

“I’m Orris Foss, by the way.”

She hesitated, then said, “Elowen.”

He repeated it, softly. “Elowen.”

She didn’t smile, but she didn’t look away either.

When she moved to wrap the pendant, he said, “It’s for my mother. My father died last week.”

She didn’t falter, didn’t make the sounds people usually made. Just met his eyes.

“Then it should be a real one,” she said.

“What does that mean?”

Elowen didn’t answer. Just wrapped the piece again, more carefully this time. Her hands slowed. She lost track of the folding once—unwrapped it, then wrapped it again, more tightly.

Foss said, “You’ve a good hand. In the silver,” he clarified. “You let it speak back.”

She didn’t look up, but she flushed a little across the cheeks.

He handed over the coin. Not Evergild marks—local silver, older, softer. She didn’t comment. Just tucked it away and gave him the parcel.

“Will you be at the stall again?” he asked.

“Sometimes.”

He waited.

Then she added, “I’ll be here next turn.”

He nodded once, as if that settled something.

“Well then,” he said, and tipped his head. “Perhaps I’ll need a wedding gift for my sister.”

He stepped away without waiting for a reply.

Elowen stood still long after he left. Her hands stayed folded at her waist, but the rhythm of the market passed through her like wind through gauze. Her work sat unfinished in the tray behind her.

She did not reach for it.

Chapter III: Off the Beaten Track

Recognition doesn’t always arrive with words.

The market had mostly cleared. The shadows had turned soft at the edges, like cloth left out in dew. A few sellers lingered, wiping down boards or folding awnings. Foss kept a slow pace, hands in his sleeves, not hovering but not in a hurry either.

He hadn’t spoken to her right away.

He waited—leaned by a post near the corner, watching the way she packed up. Not quickly, but methodically. Every clasp and cloth had its place. Her apron was already folded. Her hands bore the grey smudge of a long day’s polish, and she pushed a wisp of hair behind one ear with the back of her wrist.

When she looked up and saw him, she didn’t smile—but she didn’t look away either.

He stepped forward. “Didn’t mean to interrupt.”

“You’re not.”

“I thought I might walk with you,” he said. “If you’ve somewhere to be.”

She gave a small nod, and that was enough.

They walked side by side down the alley where the wall rose high, golden in the evening light. She carried her toolkit in one hand, the other free but close to her coat. Foss kept his pace even with hers.

They didn’t speak right away. The rhythm of their footsteps filled the space without hurrying to replace it.

At her door—a wooden arch set back from the street, plain but cared for—she turned as if to thank him.

He spoke first.

“I wanted to thank you. Properly. For the pendant.”

She met his eyes, steady now.

“When I gave it to my mother, she touched it like it carried something only she could feel. That’s rare work.”

A breath passed. Not a pause—just space.

Then he said, “It can be hard to find another to share our thoughts with, when it seems we’re off the beaten track.”

He didn’t look away.

“I’ll write to you,” he added, gently. “If that’s alright. No expectation.”

She didn’t answer at once. Just nodded—once, small, but not uncertain.

Foss inclined his head, stepped back, and let the moment close without pressing it.

Then he turned, hands still in his sleeves, and walked into the low, golden quiet of Embel Rise.

Chapter IV: The Thread Between Them

Letters, glimpses, small meetings—a bond formed in soft increments.

Elowen,

I walked the stream through Mellwain yesterday. The seedheads were bowed but not broken, just the sort of line your work carries. I wonder – do you draw before shaping, or shape to discover the line?

If I’m intruding, say so. Otherwise, I’d be glad to hear how you think.

Foss

✴ ✴ ✴

I don’t always draw first. Sometimes I touch the leaves and try to trace where they’re going. Sometimes I feel like I ruin it when I try to decide too early.

It’s not intrusion.

✴ ✴ ✴

A meeting

Foss was sent to restore the herb-beds of a low-ranking Evergild steward whose garden had soured—too much ash, too little shade. It was a dull job. But it meant he could pass through Embel Rise, if he left early and took the long road.

Elowen met him by the wall near the west gate, toolkit slung under one arm. He showed her a flattened bundle of pressed leaves, thin-stemmed and pale-edged.

“I think this is what your clasp reminded me of,” he said.

She didn’t speak, but she took the leaves. She showed him a sketch she’d made of a brooch in two pieces, a seam between.

“Would one of your marks sit here?” she asked.

He nodded, and drew a line shaped like a path that bent gently, just before the edge.

“It’s not magic,” he said. “Just a way of asking the metal to listen.”

✴ ✴ ✴

Elowen,

The smell of apple blossom is here again. At home we say it’s the trees sighing with the joy of spring. I feel it too, the way the air shifts in the chest.

Sometimes I think plants are the only ones who don’t lie. They lean toward what they need. They don’t waste time trying to be clever about it.

Foss

✴ ✴ ✴

Yes, I find myself like a plant that strains to grow towards their light. Yet the form doesn’t fit, and nor can I shape anything that echoes their truths.

I see it now. It’s not the work that’s wrong. It’s the light.

✴ ✴ ✴

A gift

A cloth-wrapped parcel arrived at her quarters. Inside, a short stem of golden yarrow, and a pressed rune on soft bark.

No note.

She wore it in her pocket until it softened.

✴ ✴ ✴

His next letter was late.

Dear Elowen,

I’m leaving the Gardens. Not out of bitterness—just clarity. I kept thinking the roots would go deeper if I stayed. But they don’t. Not in that soil.

I was always meant to go home, not to the life I left, but to the land itself.

I’d like to show you what I planted once. If the mugwort still grows in the crook by the boundary stone, then I’ve not done too badly.

Foss

✴ ✴ ✴

A visit

She travelled to Elm Cotes in the winter.

They walked the low paths in silence, spoke of nothing urgent.

He made her tea in the evenings.

She studied the way the wind moved the reeds.

Then she returned to Embel Rise. Tried to work; tried to find the line again. Her hands hesitated in places they never had before.

That told her enough.

Chapter V: What They Made

Later, in Elm Cotes. A room filled with breath and silence, and things still growing.

Foss lifts a kettle from the hook above the fire. His sleeves are rolled, palms damp with mist from the garden. Outside, snowdrops crowd the ditch-edge like they’ve always belonged there.

Elowen stands at her bench, a stone held gently in the jaws of her pliers. Beside her, a half-finished brooch, a folded letter, and a design not yet made – precise as joinery, but meant to be worn.

On the shelf above the window, in a flat wooden box, lie the old letters. Pressed leaves between some pages. One still smells of fennel root. She’s never shown them to anyone.

Some months earlier, Foss had gone with her to Kellack Wheal. Her father, Derrick, had clasped his hand with both of his, said,

“Take care of what matters. That’s all I ask.”

Her mother had been polite, if a little tight-lipped.

“I’d have thought you’d stay with the Evergild. But if you’re content in the wilds…”

She hadn’t asked questions after that.

They hadn’t married. No ceremony, no binding words. But Elowen kept a place clear for his cup and laid her tools beside his, and he hummed her name into verses when he stirred the tinctures.

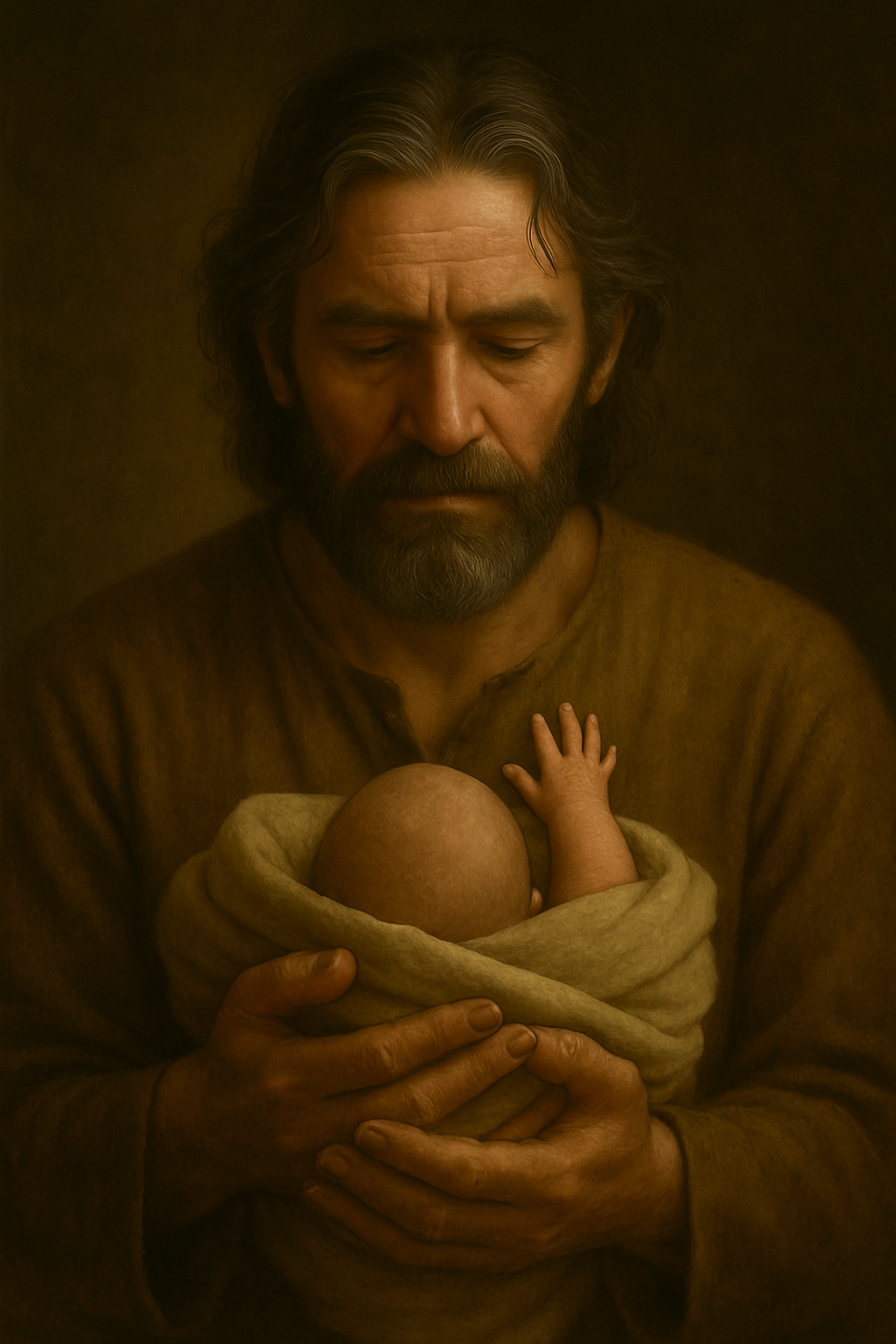

When Lowen was born, Foss held them like they were a seedling.

And when he left—he left something behind. Not just people, but the shape of something grown with care.